Build Ahead

Inside the 2025 Senior Research Fellows Retreat

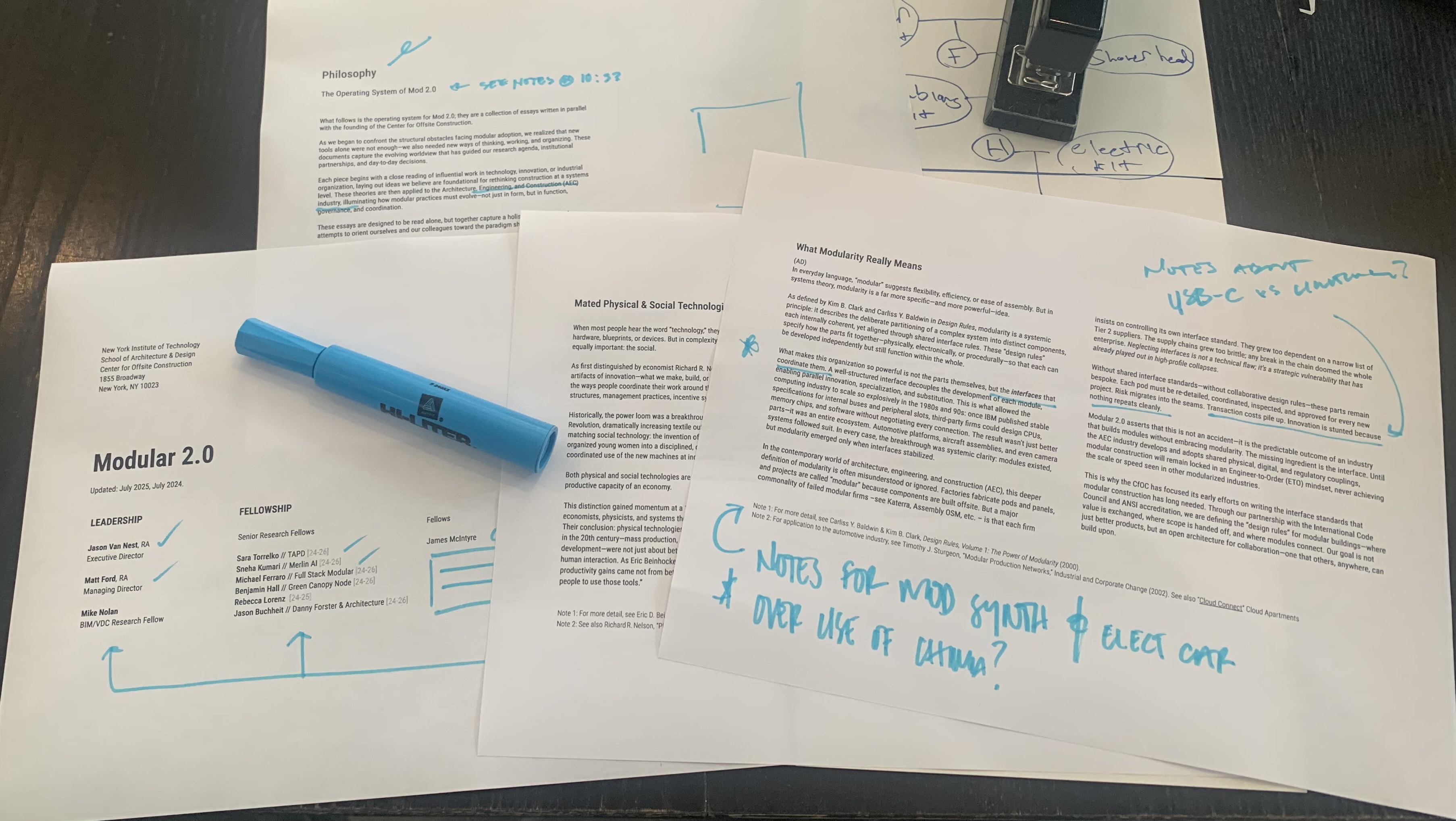

Each year, the Center for Offsite Construction at NYIT convenes its appointed Senior Research Fellows for a retreat that functions as both a reunion and a crucible. It’s a moment when returning Fellows reconnect, new Fellows are welcomed into the fold, and the entire group takes on its most vital internal task: refining Modular 2.0.

This year’s retreat, held virtually in July, was anything but routine. Designed to interrogate the newly drafted “Philosophy” section of Modular 2.0—a framework that defines the intellectual operating system behind the Center’s research roadmap—the event gave participants a rare opportunity to shape the direction of a growing field. “These essays want to get published,” said Jason Van Nest, Executive Director of the Center, in his opening remarks. “They’re not meant for internal consumption. They’re for our partnerships. They’re for industry. They’re for anyone trying to understand how offsite becomes a scalable construction methodology in North America.”

The format was simple and playful. Each essay had a designated provocateur—a Senior Research Fellow (SRF) who had pre-read the work and would open the discussion with both a summary and a set of pointed questions. Then came open critique, what Van Nest called the "tomato-throwing" portion of the session: a no-holds-barred conversation to identify flaws, gaps, and areas for growth. It was, in the words of Alexandra Donovan, a deliberate effort to "accelerate smart disagreement."

Modularity Begins with Interfaces

Donovan, the Design & Innovation Lead at Assembly OSM, led the first discussion on "What Modularity Really Means." She embraced the essay’s thesis that interfaces—not components—are the true enablers of modularity, likening them to software APIs. But she quickly pressed the group on practical issues: Which connections matter most? Who decides? And how do you motivate companies to make their proprietary IP open source?

“There’s a real risk of freezing interfaces too early,” she cautioned, “before emergent solutions have time to evolve.” Still, Donovan saw potential in gathering bottom-up data from companies already working on connections in the field: "What interface points have your teams developed or are working on? What's working? What seems promising?"

Mike Ferraro, VP of Design at FullStack Modular, responded with urgency. “I would love to go buy sub-assemblies from a catalog,” he said. “But over-focusing on IP gets people lost. modular design teams risk always designing their connections to one job. We can use these collaborations to build a platform, and avoid the trap of one-off collaborations."

Sara Torrelko, founder of Modutize and a veteran of multiple modular factory organization efforts, added a note of caution: “We must be careful that we are not asking companies to deprioritize what they see as their competitive advantage. Unless the financial and legal environment changes, they may have no reason to share.”

Scaling Without Size

Benjamin Hall, a returning Fellow from Green Canopy Node, facilitated the second discussion on the essay "Scaling Without Size." The piece argues that a federated network of modular producers—bound together by common standards—can achieve the scale benefits of consolidation without monopolistic control.

But Hall pushed back. “We must take care not to underestimate the role of centralized planning,” he said. “Coordination doesn’t emerge from… nothing. You need referees, not just players."

Van Nest responded with an analogy: “We must help colleagues evolve the way that they have already with federated BIM (models). With architects, and a bevy of engineers all modeling in one environment… No one “owns” the model, but everyone benefits when the parts fit together. The same conventions apply to products in Tier 2 and Tier 3 supply chains.”

Donovan and Ferraro both backed the idea of federated strength, especially when it came to supply chain resilience. “What assemblers in offsite need most (to scale) is redundancy,” said Ferraro. “Currently, if one project's bespoke supplier gets hit by a truck, that project can be sunk. But… If five vendors can make the same pod to the same spec, then you keep building."

Over-Connectivity and the Spaghetti Problem

Sara Torrelko took the lead on "Over-Connectivity," a concept that describes the construction industry’s tangled web of stakeholders, regulations, contracts, and supply chains. She likened the industry's inertia to the early days of television—an innovation held back by outdated infrastructure and incompatible systems.

“Every channel has to agree the innovation is worth it,” she said. “And in our industry, right now, they don’t."

Her challenge: clarify the roadmap and offer calls to action tailored to each actor—banks, contractors, code officials, developers. “This vision isn’t about blame. Its about a solution -- alignment,” she said.

Connor Bailey, a GC-side Fellow from DPR Construction, immediately resonated. “The whole AEC industry is currently built off (service-based) contracts. And today's contracts were not written for offsite. Without better contracts, we'll never align the lenders and insurers that depend on them.” He shared a story about building a hospital patient tower where modular bathrooms were rejected in early phases because the owner's contractual pressures shied away from single vendor dependencies — even if product freedom meant abandoning a more efficient delivery.

“We need new legal frameworks that treat modular risk differently,” Bailey said. "Right now, we're trying to innovate inside contracts that assume you're buying drywall and studs."

Degrees of Freedom vs. Degrees of Possibility

Mike Ferraro opened the conversation on "Degrees of Freedom," an essay adapted from concepts in complex systems thinking. His message was practical: “Freedom of choice is meaningless without viable options."

In other words, the market can’t offer meaningful choice without a preexisting catalog of viable, pre-approved products. Ferraro called for the creation of a centralized repository—an open-source database of modular assemblies, connections, and certifications.

Sara Torrelko seconded the need. “Right now, if I want to spec a modular connector, I have to reverse-engineer it from scratch. That’s ridiculous. Even in conventional construction, I can search UL databases or draw from codebooks. Modular has no equivalent."

Matt Ford, the Center’s Managing Director, underscored the point. “That's exactly why we started with bathroom and kitchen pods. They're insulated from regional load conditions. We can win those battles first, then move outward."

The Call to Action

Throughout the retreat, the question loomed: What comes next? The essays were strong, Fellows agreed, but needed clearer through-lines, plainer language, and more actionable steps. “I want to send these (essays) to subcontractors and not have them get lost in paragraph one,” Ferraro noted.

Others, like Donovan and Hall, asked for medium-expanding formats—podcasts, visuals, Airtable-style databases. The goal wasn’t to dilute the ideas, but to amplify them.

As the retreat wrapped, Van Nest laid out the stakes: “We’re not just drafting philosophy. We’re setting an intellectual foundation for the future of this industry. These essays aren’t opinion pieces—they’re operating system documentation. And they only matter if they’re legible.”

The next steps include finalizing and publishing the revised essays, maybe recording something interesting(?!), connecting th work to the Mod 2.0 Research Radmap in a deeper way, and preparing for a March 2026 in-person symposium where ideas seeded here will take further root.

If there was a shared theme, it was this: The modular industry doesn’t need another white paper. It needs a common language, a shared infrastructure, and a coalition ready to build it.

At the Center for Offsite Construction, that coalition is already forming—one retreat, and one idea, at a time.

More Posts

All PostsFeb 16, 2026

What's Critically Missing in the Road to Housing Act

Feb 16, 2026

The CfOC's Lessons from Advancing PreFab 2026

Feb 01, 2026